Mickey Mouse has technically entered the public domain, but does that mean anybody can use the iconic figure? Is a mouse-themed horror movie on the way? Well, not necessarily. Moving forward, Disney will most likely be exerting control over the character via trademark law, rather than copyright law... but what does this mean?

I promise you that the answer is far more interesting than dry legal terms like "copyright" and "trademark" suggest.

On January 1, 2024, Disney's most valuable character and defacto corporate mascot, Mickey Mouse, entered the public domain. Traditionally, the public domain is where the rights holder, in this case, Disney, no longer has exclusive control over the character. That would make Mickey public property, and any creator would be free to do with him what they pleased. But for a number of reasons, this case will not be so simple.

Explaining copyright and trademark law

The concept of public domain is a simple one. An artist is entitled to the revenue generated by the art they make, and they have a right to control how that art is used. But copyright doesn't last forever; after a while, a piece of art becomes public property, rather than being the property of whoever made it. That's why you do not have to pay the estate of William Shakespeare to stage one of his plays.

Generally speaking, artists do not live long enough to see their work fall into the public domain because the purpose of the public domain is not to take intellectual property away from creators. It's to ensure that the artistic canon of humanity is the property of humanity. But when intellectual property is held by a corporation, rather than an individual, as in the case of Mickey and Disney, that corporation could outlast any natural human lifespan and fight to retain its intellectual property in perpetuity.

Disney has repeatedly shown a willingness to do that. 1998's Copyright Term Extension Act was nicknamed the "Mickey Mouse Protection Act" because it came as a result of Disney's lobbying. It extended Mickey Mouse's copyright protection, which would've expired in 2004 otherwise.

This time, Disney has chosen a different tactic for protecting Mickey: Trademark. Trademark law protects brands, rather than art, to make sure consumers know who they're buying from. Corporate logos are protected under trademark law to ensure they're not misused. For example, the Coca-Cola logo was designed in 1885, putting it well out of copyright; Trademark is the reason that you cannot use Coke's logo to sell generic soda.

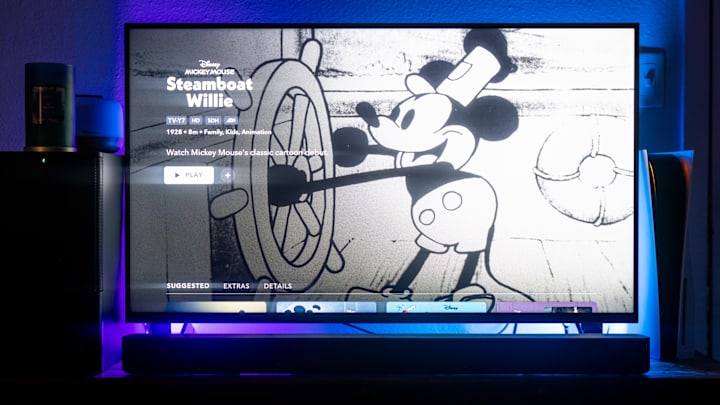

This is why Disney added a clip from Steamboat Willie, the film in which Mickey first appeared, to its title cards.

The clip is now heavily associated with the company, which officially makes Mickey a trademark-protected signifier of Disney's brand. And trademark law doesn't have an expiration date.

What legal support does Disney have for keeping control over Mickey Mouse?

What does it mean, in practical terms, that Mickey is protected under trademark rather than copyright? Theoretically, it means that Mickey Mouse is free to use, as long as you're not implying a connection to Disney. But with Mickey Mouse being so closely connected to Disney, is it possible to use Mickey in any way that does not imply a connection to Disney?

Sooner or later, this question will be litigated, and we'll have an answer. But that will have to wait until someone with the resources to go up against Disney tests the theory in court.

With legal questions such as these, we can sometimes rely on precedent to predict how things will go. So, are there any cases that provide such a precedent? Not exactly, but there's a famous case that's close.

The Sherlock Holmes stories were published over a forty-year period between 1887 and 1927, meaning that until 2023, some Sherlock Holmes stories were in the public domain, while others were not. In Klinger v. Conan Doyle Estate, Ltd. the author's estate claimed that any unauthorised use of the characters of Holmes and Watson relied on character elements introduced in the later stories that were still under copyright.

In Klinger, the court found that agreeing with Doyle's estate would mean granting perpetual copyright to any character, as long as the character was continually in use. That was an unreasonable precedent to set.

This shows that the courts are reluctant hear arguments that would make an end-run around public domain. On the other hand, the legislature has shown a willingness to bend over backwards to protect Disney's intellectual property.

The Sherlock Holmes case also shows the difficulties that arise when some parts of a series are in the public domain and others aren't. Since the vast majority of Mickey Mouse cartoons will remain under copyright for some time yet, it will probably get very complicated whenever someone attempts to use Mickey Mouse.

What legal protections do the people have?

Between complicated copyright laws and the dominance of trademark, is there any hope for creators looking to use Mickey Mouse in the future? There is one legal construct that's gotten a little lost in this debate, and that's fair use.

Fair use is basically the principle that copyright does not exist to prevent intellectual property holders from being made fun of. If you write a story with the exact same plot and characters as an existing story, that's a prima facie copyright violation. But if your story is a parody, common sense would say that's okay. After all, we do not want to outlaw parody.

However, copyright law does not recognize that distinction. According to the letter of the law, a parody is a copyright violation, and a thin-skinned rights-holder could use copyright law to shut down any parody of their work.

Fair use is a set of circumstances in which it's okay to violate copyright. Those circumstances include, but are not limited to, parody. The problem with fair use is that it's a legal custom, not a statute, which means it's a defence you can use if you're sued, but it will not shield you from being sued in the first place. Thankfully, there's a great deal of case law spanning the centuries that defines the parameters of fair use.

Perhaps most relevant here is the Supreme Court case of Campbell v. Acuff-Rose Music, Inc.. Hidden behind that deceptively prosaic name is a case that established the hip hop group 2 Live Crew's right to release a vulgar parody of Roy Orbison's "Oh, Pretty Woman." The Campbell decision overturned a court of appeals decision that found that 2 Live Crew had taken the "heart" of "Oh Pretty Woman" to form the "heart" of their track, harming the market for the original.

Presumably, by the Court of Appeal's logic, 2 Live Crew would've had to find a way of referencing "Oh Pretty Woman" without implying a connection to it. This would be an impossible needle to thread, just as using Mickey Mouse without implying a connection to Disney would be an impossible needle to thread.

Fair use gives us the right to use Mickey in parody. Fair use is the reason that a cynical, vulgar, Scientology-defaming Mickey Mouse has been a running gag on Last Week Tonight with John Oliver since the beginning of 2023.

If one cannot use the Mickey Mouse character without implying a connection to Disney, why bother trying? Well, many people believe that Mickey Mouse belongs to the people as much as he does to Disney. Because of fair use, anyone who uses Mickey Mouse can make the inevitable Disney connection an essential part of the work, rather than tying themselves into knots trying to excise it.

We'll have to wait to see exactly where the courts stand on this complicated issue, but it seems likely that Disney will use every card in their deck to make sure they can keep control of the character that built their empire.

Keep an eye on Ask Everest for answers to all the Internet's questions.